How I’d Run a SaaS Pricing Project from Scratch

Plus: The "core constellation" of pricing stakeholders.

Welcome back to Good Better Best!

It was a busy week, so we’re back with a weekender addition. If you’re just waking up, grab some coffee and settle in. If you’re already into the weekend activities, bookmark this one for later.

This is my current playbook for working through pricing projects. It includes some of my favorite frameworks, along with some awesome lessons from Ulrik at the end.

Let’s get to it.

Why billing is now a product problem

Brandon Walsh (HubSpot, Intercom) and James Brown (Metronome) do a product-to-product deep dive in this episode of Unpack Pricing. They dig into how usage-based pricing is transforming product strategy, team roles, and the customer experience itself. If you're navigating hybrid models, outcome-based pricing, or build-vs-buy infrastructure decisions, don’t miss this one.

How I'd Run a Pricing Project from Scratch

Pricing projects have a funny way of finding people that never asked for them.

If you're working in product, product marketing, or bizops at an early-stage SaaS company, there's a chance you've experienced this scenario:

Leadership decides pricing needs attention, but with no dedicated pricing function (or budget for a consultant) the project lands in your lap.

The challenge with pricing projects is that they combine two things that, together, are a recipe for chaos:

Urgency: You need to make decisions quickly.

Ambiguity: The path forward is murky.

This uncertainty can be paralyzing, especially when you're already juggling other responsibilities. Complicating matters, pricing advice is rarely one-size-fits-all.

The reality is that the scope and specifics of your pricing project should be highly specific to your company's stage, team, and specific opportunity.

Let me walk you through the framework I'd use to tackle a pricing project systematically, breaking it down into three core areas that will help you focus your efforts and make meaningful progress.

Step 1: Diagnose Your Growth Stage

Before you dive into pricing mechanics, you need to understand where your company sits in its growth journey. This context will fundamentally shape what you're trying to achieve with pricing and how you should approach the project.

I use a three-phase framework adapted from Mike Maples that breaks down company growth into distinct stages, each with its own pricing objectives and constraints.

Value Hacking Phase: Prove Demand

In the value hacking phase, companies are working to establish product-market fit. You might have some initial customers and positive signals, but you're still fundamentally trying to prove that people will actually pay for what you're building.

During this phase, your pricing strategy should be dead simple. You shouldn’t be trying to optimize for maximum revenue or create the perfect scalable model.

Your goal should be to get something out there that customers will actually buy.

This might mean starting with a basic flat fee, a simple per-seat model, or even just a single pricing tier. The key is removing friction that could prevent potential customers from buying. You're gathering data about willingness to pay and learning about your customers' value perception, which will inform more sophisticated pricing strategies later.

It’s unlikely you’ll be tasked with a pricing project at this phase, but it still provides helpful context for the phases ahead.

Growth Hacking Phase: Balance Acquisition and Retention

Once you have evidence of PMF and feel genuine pull from the market for your product, you’ve entered the growth hacking phase. This is where pricing becomes more strategic and complex because you're trying to create a scalable growth model.

Your goal should be to create a model that allows you to acquire new customers efficiently while also retaining and expanding existing customers.

During the value hacking phase, it’s okay to over-index for acquisition, but now you need to think about long-term customer value and creating a model that grows as your customers grow and derive more value from your product.

HubSpot provides an excellent example of this phase.

In the early days, HubSpot used a flat fee pricing model. This worked for initial customer acquisition but created problems downstream. Early customers were primarily SMBs, which have high churn rates. The flat fee model meant that customer value didn't grow over time, and made it difficult to overcome this natural churn to achieve strong net retention.

To address the challenge, HubSpot evolved to a two-axis pricing model that combined a base fee with usage-based components. This hybrid approach allowed them to capture expansion revenue as customers grew their contacts database and got more value from the platform. This helped solve the net retention problem, and powered an IPO in 2014.

While all situations are different, the Growth Hacking Phase is a good time to look at a hybrid pricing model if you don’t have one already.

Profit Hacking Phase: Expand Revenue Surface Area

The profit-hacking phase begins once you have a mature pricing model that's working effectively for both acquisition and retention.

At this point, you're looking for ways to drive incremental revenue and expand the surface area of your product beyond your core offering.

This phase can take many forms, but the common thread is finding new revenue opportunities that leverage your existing customer relationships and market position. This could mean:

Launching entirely new products that serve adjacent needs for your existing customer base.

Developing add-ons or modules that extend your core product's functionality. These add-ons start as separate products that customers can purchase independently of their main subscription. Over time, successful add-ons might be folded into the main product to justify price increases, or they might evolve into standalone products in their own right.

Developing professional services offerings for complex product use cases that benefit from implementation support or strategic guidance.

The key insight for the profit hacking phase is that you're not trying to fix a broken pricing model. You're looking for ways to extend a model that's already working well.

Returning to HubSpot — after the core Marketing Hub was established, HubSpot launched they launched add-ons like Reports, Ads, and Website tools. These add-ons served specific customer needs that weren't addressed by the core platform, and customers could purchase them separately. Eventually, many of these add-ons were integrated into the main product tiers, allowing HubSpot to justify price increases while providing additional value to customers.

After that, HubSpot launched Sales Hub, starting the Value Hacking phase all over again with an entirely new product.

Step 2: Identify Your Area of Impact

Once you understand your growth phase and objectives, you need to figure out where you can actually make an impact. Not all aspects of pricing are within your control or relevant to your growth stage, so it's important to eliminate variables that aren’t worth focusing on.

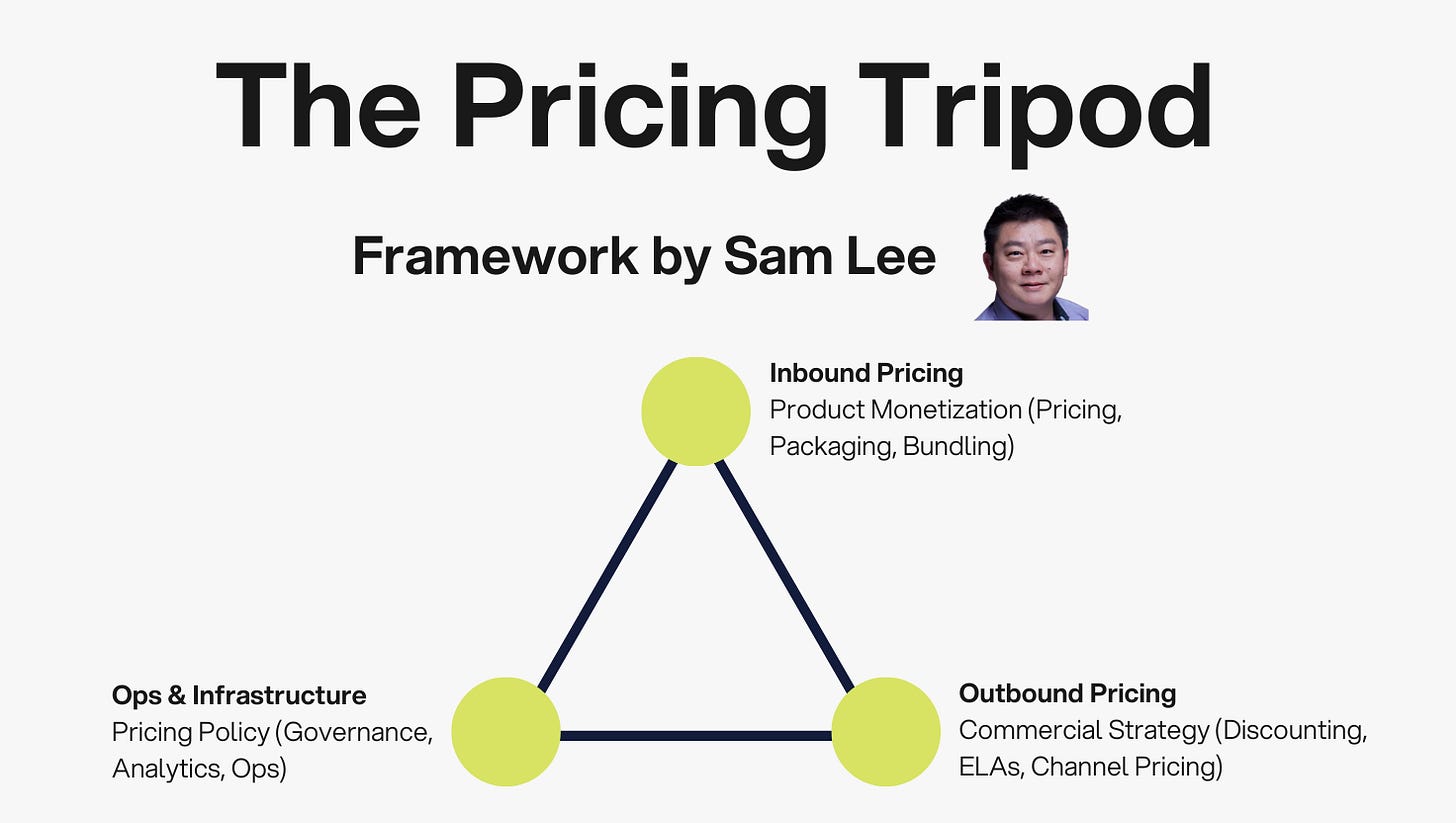

My favorite framework for this is the Pricing Tripod, a framework I learned from Sam Lee, VP of Pricing Strategy and Product Operations at HubSpot. His framework organizes pricing work into three distinct areas, each requiring different skills and typically owned by different functions within an organization.

Inbound Pricing: Product Monetization Strategy

Inbound pricing encompasses your core product and pricing strategy decisions. This includes:

How you package your product into different tiers

What pricing metrics you use

How you structure your plans

What features you include at each level

This is the strategic foundation of your pricing model, and is essentially where product meets strategy.

If you're a product marketer or product leader, this is most likely where you'll focus your efforts. It aligns well with your existing skills around product positioning, customer segmentation, and value proposition development. You likely have insights into customer needs, competitive dynamics, and product capabilities that will be valuable for these decisions.

Outbound Pricing: Commercialization and Price Realization

Outbound pricing covers everything that happens between your list price and the actual price customers pay. This includes:

Discounting strategy

Partner channel pricing

Enterprise licensing agreements

Any variables that affect your final realized price in the market

This area typically requires close collaboration with sales operations, channel partners, and the broader revenue organization. While your input might be valuable, this probably isn't where you'll have the most direct control or immediate impact (unless you’re in BizOps, RevOps, or a similar role).

Ops and Infrastructure: Governance, Measurement, and KPIs

This area focuses on how you measure pricing performance against business objectives and what metrics you track to evaluate success. This includes the KPIs you monitor, how you report on pricing performance, and how pricing decisions align with broader business goals.

The focus here often shifts based on broader business priorities—for example, many SaaS companies shifted their focus from pure revenue growth to profitability metrics following the pandemic. Again, if you’re in Product or Product Marketing, this probably isn’t where you’ll have the most impact.

Step 3: Pressure-Test Your Pricing Strategy

By now you’ve likely realized that Inbound Pricing (or Product Monetization) is the area where you will have the most impact. This is also where most pricing projects start from my experience, and where 90% of pricing content is focused.

But Product Monetization is its own beast with a mix of levers to pull to find meaningful improvements. Here’s the sequence I would run through to assess opportunities.

Plan Mix: Reassess Your Plans Using JTBD

Start by examining your current plan structure with fresh eyes. Each plan should solve a specific Job-To-Be-Done for a clearly defined customer segment. This might sound obvious, but I see so many companies offer plans that feel extraneous, and don't seem to serve a real purpose.

In an ideal world, every plan should be designed for a real customer segment with specific needs and willingness to pay. This doesn't mean you can't use psychological pricing principles (like anchoring or the compromise effect) but the foundation should be genuine customer value rather than pricing gimmicks.

Plan consolidation (or expansion) is one of the more common changes we see in the PricingSaaS database. Simplifying your plan structure or adding to it to serve new buyers can improve customer clarity and decision-making while making your pricing easier to communicate and sell.

Usage Thresholds: Dial Your Consumption Metrics

Most SaaS companies have usage-based components in their pricing, whether that's seats, contacts, API calls, storage, or some other consumption metric.

While you probably won't change your primary pricing metric (that's a major strategic decision), you can optimize the thresholds that trigger upgrades or additional charges.

Start by analyzing your actual usage data to understand how different customer segments consume your product. Your usage thresholds should align with natural breakpoints in customer behavior rather than arbitrary round numbers. For example, if most of your small business customers use 8-12 seats, having a plan that includes 10 seats makes sense. If they typically use 15-20 seats, your 10-seat plan might be creating unnecessary upgrade friction.

Look for arbitrage opportunities where you can offer significantly more value than competitors without dramatically increasing your costs.

My favorite example is Zoom's freemium strategy. When they entered the market, most competitors offered free trials for 2-3 users. Zoom allowed 50 users in their free plan, which looked very generous. They balanced this by limiting meeting duration to 40 minutes, allowing companies to test the product in realistic conditions while ensuring any serious business would need an upgrade.

Feature Packaging: Map Value and Willingness to Pay

Feature packaging requires understanding not just what customers want, but what they're willing to pay for — and these aren't always the same thing.

Enter the value matrix.

The Value Matrix maps relative preference against willingness to pay to categorize features into four buckets:

Core Features: Everyone wants them, but aren’t willing to pay a premium for them. These should be included in your base plan.

Value Drivers: Customers both want them and are willing to pay a premium for them. These are your primary way to drive upgrades from capabilities (rather than consumption). These features usually help solve a new “job” that can anchor an upgraded tier for a different buyer profile.

Add-Ons: Not everyone wants them, but those that do are willing to pay for them. This is often underutilized territory for SaaS companies. Importantly, this can include product features and professional services.

Forgettables: These are features that customers don’t really think about.

Price Points: The Final Adjustment

Price points should be the last thing you optimize, which might seem weird. If your underlying model is working well, your actual price points shouldn’t matter that much.

Price point optimization usually requires deep market knowledge and competitive analysis. You need to understand not just what competitors charge, but how customers budget for solutions like yours and what price points feel reasonable within your market context.

If you have fundamental issues with your pricing model: a confusing plan mix, misaligned usage thresholds, no meaningful feature differentiation — adjusting price points won't solve those problems. Fix the foundation first, then fine-tune the pricing.

Bringing It All Together

When a pricing project lands in your lap, resist the urge to immediately jump into the weeds. Starting from a birds-eye view and identifying what you can and can’t control will help alleviate the decision paralysis that can come with projects like this.

Importantly, each of the elements of pricing strategy mentioned above can and should be evaluated with qualitative and quantitative research. My favorite approach is doing batches of customer and prospect interviews first, then pressure-testing the findings with quantitative surveys.

To recap:

First, understand where your company is in its growth journey and what you're actually trying to achieve with the pricing project.

Second, identify where you can have the most impact given your role and expertise. Focus your efforts on areas where you have both control and relevant skills rather than trying to tackle everything (or pull in every possible stakeholder).

Finally, work through the specific levers methodically, starting with plan mix and working your way through usage thresholds, feature packaging, and price points. This sequence ensures you're building on a solid foundation rather than trying to fix surface-level issues while underlying problems remain.

🎯 Expert Insight

When I first started working on pricing projects, I made a critical mistake that took me years to fully understand. I treated pricing like an Excel problem — something you could solve with the right combination of formulas, data, and coffee-fueled late night spreadsheet sessions. I was wrong.

The reality I've come to embrace is that pricing is fundamentally a design challenge, not a computational one. And like any good design project, it requires cohesion and integration across your entire organization. This shift in perspective has transformed how I approach pricing work with teams.

The “Core Constellation” of Internal Teams

Let me be clear about something: if you're trying to solve pricing in isolation, you're setting yourself up for failure. The most successful pricing projects I've led have involved what I call the "core constellation" of internal teams—Product, Sales, Customer Success, Management, and Finance. Each brings a critical perspective that you simply can't replicate from your desk.

The magic happens when you get the head of Product and the head of Sales to develop an extremely strong shared understanding of your business goals and product packaging. I've seen too many pricing initiatives collapse because these two functions were operating from different playbooks. When they're aligned, everything else falls into place.

The Rhythm of Pricing Work

The scheduling and process side of pricing has evolved significantly in my practice. The ideal state I aim for with clients is establishing what I call "The Four Questions of Pricing" as an ongoing capability. These questions are:

What should we build next?

How should we package that into sellable products?

How should we price that? (e.g., designing the pricing model)

How much should we price that? (e.g., setting the actual price points)

I've also learned to adjust iteration cycles based on deal size: six months for ACVs over $50K, three months for deals under $50K, and monthly cycles for $10K and below. The higher the velocity, the faster you can learn and adapt.

For customer validation interviews, I typically schedule three to five sessions, each lasting thirty to forty-five minutes. This gives you enough data points without overwhelming your schedule or your customers.

What I've Learned About the Human Side

Perhaps the most important lesson I've learned is that pricing work is inherently collaborative and iterative. I've seen brilliant individual contributors struggle with pricing projects because they approached it as a solo endeavor. The insights emerge from the conversations, the tensions between different perspectives, and the process of building shared understanding.

Customer involvement is crucial, but it's not just about surveys or focus groups. Some of my best insights have come from postmortem conversations with customers who ultimately didn't buy—they'll tell you things that successful customers never will.

I've also learned to be more adaptive in my approach. Market conditions change, products evolve, and customer expectations shift. The pricing framework that worked brilliantly six months ago might need significant adjustments today. This requires what I call structured flexibility — having processes robust enough to handle change while maintaining the discipline to make data-informed decisions.

Thanks for tuning in and see you next week!

Have thoughts on this post? I’d love to hear them. Hit reply or drop a comment.